Picture a gymnast performing a floor routine. Their options for movement are almost infinite — they can run, flip, cartwheel, leap, or twist.

Any move they make, however, can be broken down into three broad categories of movement, which anatomists describe using the three planes of motion: They might move forward or backward or shuffle or turn to their left or right. (They might also combine any of these types of movement, of course, but more on that later.)

Understanding how your body moves within these planes will give you another tool that can help you make your workout safer, more effective, and more fun.

What Are the 3 Planes of Motion?

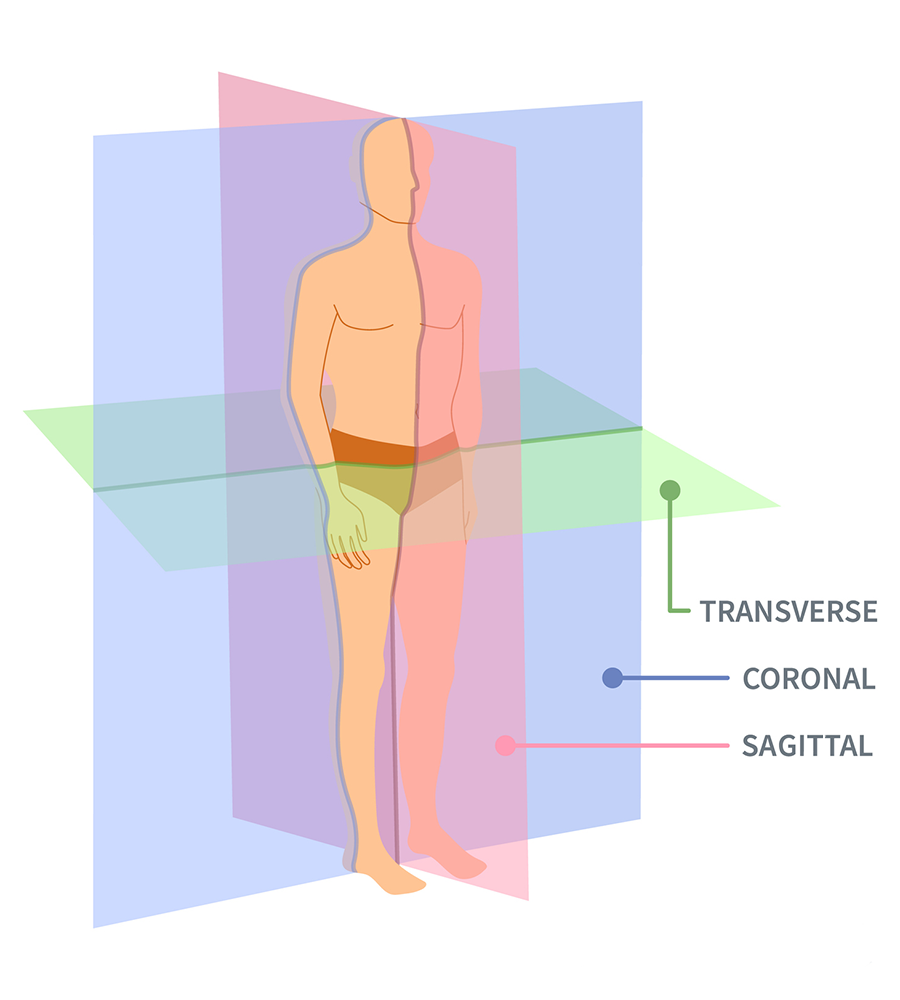

The planes of motion are a way to describe and understand human movement of all kinds — from working out to dancing to breathing — through a more precise, anatomical lens. You can think of these planes as sheets of glass that divide the body into different halves:

- Sagittal plane: Separates the body vertically into left and right halves

- Frontal plane: Separates the body vertically into front and back halves

- Transverse plane: Separates the body horizontally into top and bottom halves

Any movement you perform that’s broadly parallel to any of those body planes is considered to occur in that plane of motion.

Confused? Stick with us.

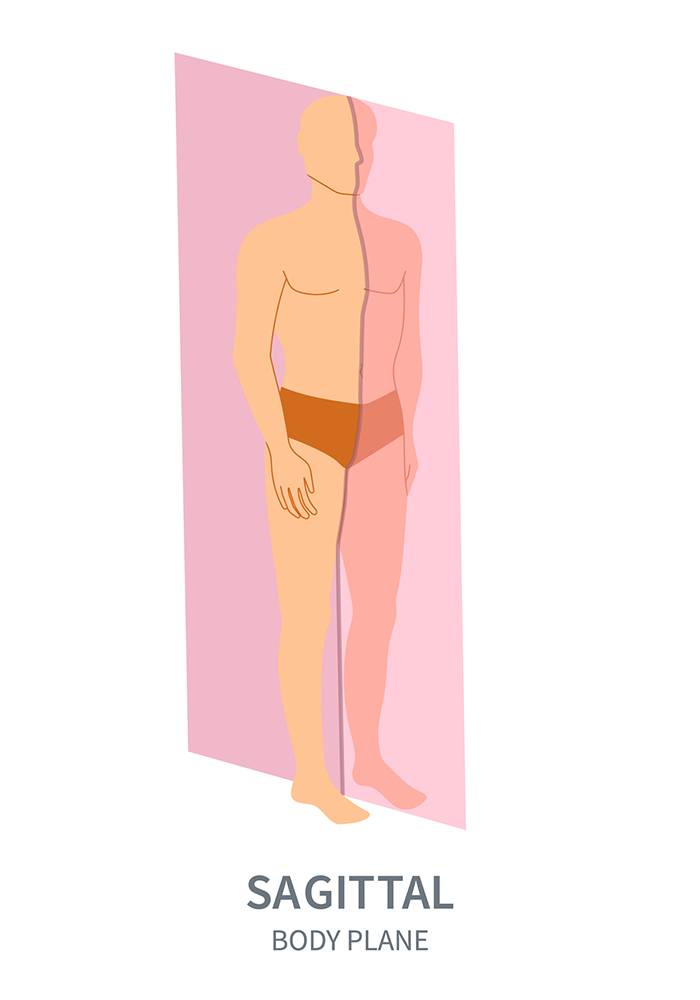

1. The sagittal (longitudinal) plane: forward, march

The plane we encounter most often in life — and probably the one that’s easiest to understand — is the sagittal, or longitudinal plane. This is the plane that cuts you in half vertically at your center line, separating the left and right sides of your body.

Any movement where your limbs or spine move along this line — or parallel to it — is considered sagittal, or longitudinal. (Sagittal derives from a Latin word meaning “archer.” Picture shooting an arrow from a bow at a faraway target, and you get the idea.)

Movements in the sagittal plane:

Many classic gym moves are considered sagittal-plane-dominant: lunges, squats, curls, crunches, sit-ups, and push-ups. In these exercises, your arms, legs, or spine all move parallel to that central, sagittal plane. (Front and back flips are also sagittal.)

Day-to-day moves like walking — where your arms and legs swing forward and back — are also mostly sagittal. It’s the plane most of us are most comfortable in.

From a therapeutic, or anatomical perspective, flexion and extension — curling the spine forward or bending backward — are classic examples of sagittal movement.

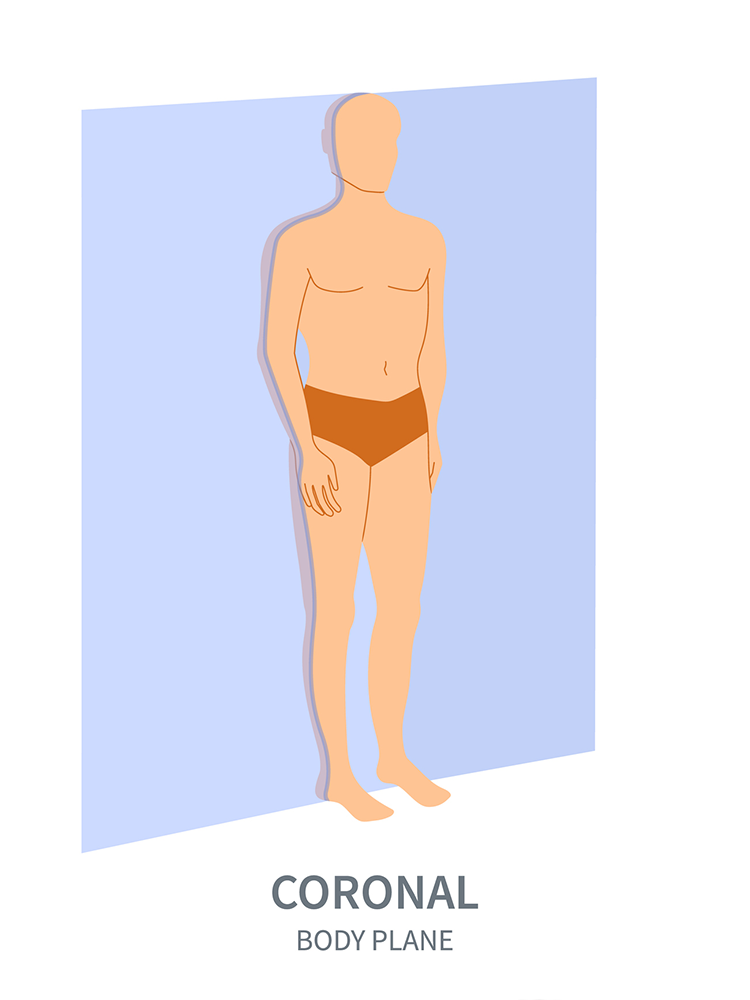

2. The frontal (coronal) plane: left, right, and center

Tougher to picture but equally important is the frontal or coronal plane. This is the plane that runs vertically through the body, one side to the other, and separates the front and back sides of your body.

Picture yourself standing on a narrow ledge with the entire back side of your body — heels, calves, glutes, upper back, elbows, the backs of your hands and the back of your head — pressed against a wall. Any move you can make while maintaining those contact points is a frontal plane move.

Movements in the frontal plane:

Frontal plane movements include the side-step, or side shuffle, extending your arms out to the sides, tilting your head left and right, or side-bending your entire torso one way or the other. If you’re agile and brave, cartwheels also occur in the frontal plane.

The lateral-shuffle movements in sports like basketball and tennis, are all frontal. Side-lunging is also a frontal movement.

Anatomically, abduction — or raising your arm or leg away from your center line — is a frontal plane move.

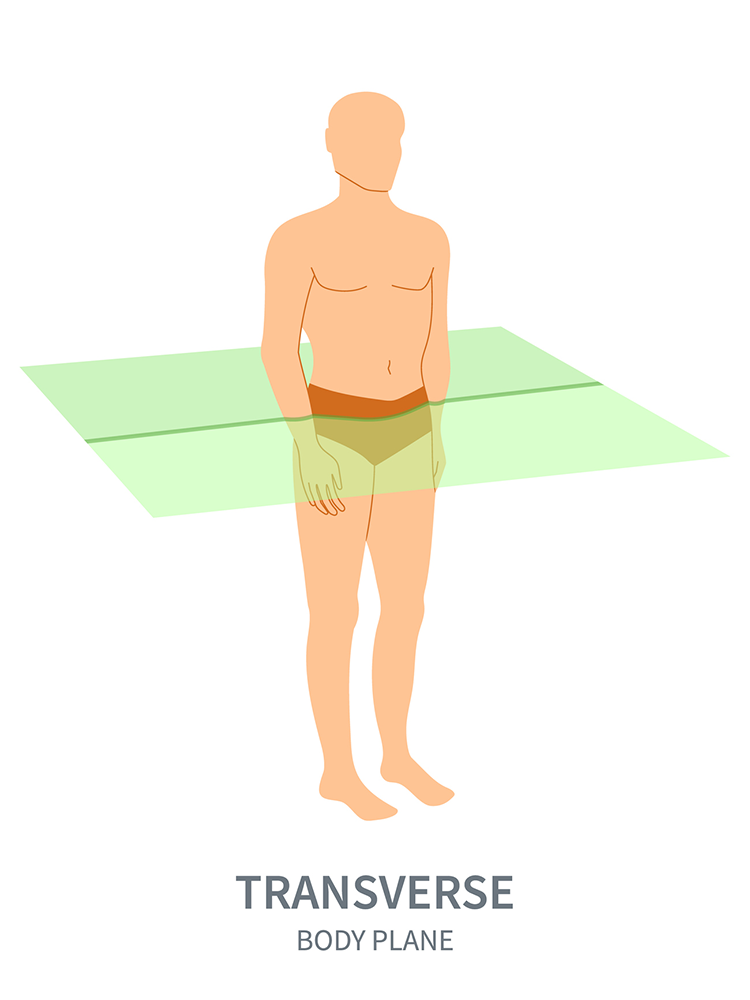

3. The transverse (axial) plane: twist and shout

The final plane of motion is one we don’t think about much, even though we move through it all the time. It’s the plane that runs parallel to the floor, also known as the transverse or axial plane.

This plane encompasses rotation around your vertical axis. A ballet dancer’s pirouette is a classic example: Her entire body is turning around a single, still point.

Movements in the transverse plane:

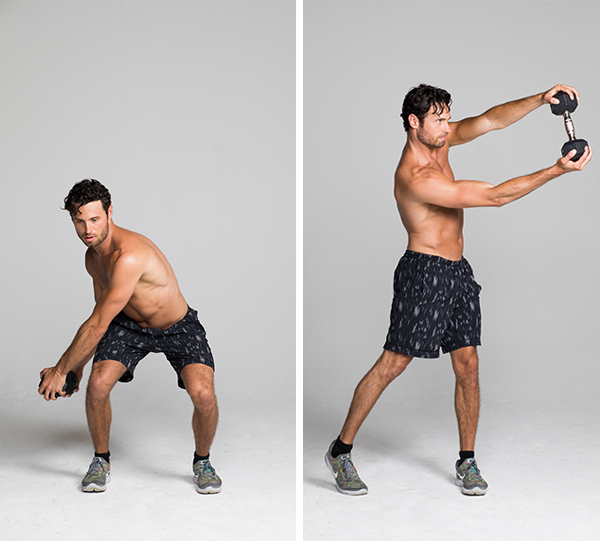

We often see transverse plane movement in warmups — hip circles, neck rolls, ankle circles, and trunk rotations are all good examples. Some core movements — such as Russian twists or bicycle crunches — are transverse-plane dominant, as are many of the rotating stretches in yoga.

Many of the most powerful athletic moves you can do, such as swinging a bat or a racquet, throwing a discus, or executing a roundhouse kick or a hook punch in MMA, are transverse plane moves; if you want to generate power, the transverse plane is your ticket.

Anatomically, rotating any joint along an axis is a transverse plane move.

Anatomical Terms

Jargon alert: The following terms — usually used in medical or therapeutic settings — describe various locations, directions, and types of movement on the body. In all cases, assume that you’re referencing a person standing upright with their palms rotated forward, thumbs pointing outwards:

Directional terms

| Anterior | Towards the front side of the body |

| Posterior | Towards the rear of the body |

| Deep | Farther from the surface of the body |

| Superficial | Closer to the surface of the body |

| Distal | Farther from the center of the body or the origin of a body part (i.e., The ankle is distal to the knee, while the toe is distal to the ankle.) |

| Proximal | Closer to the center of the body or the origin of a body part (i.e., The shoulder is proximal to the elbow, while the elbow is proximal to the wrist.) |

| Inferior | Towards the feet |

| Superior | Towards the head |

| Lateral | Away from the center line of the body |

| Medial | Towards the center line of the body |

| Median | The midline of the body |

Movement terms

| Abduction | The moving of a limb away from the center line of the body (i.e., from standing, raising your arm out to the side) |

| Adduction | The moving of a limb towards the center line of the body (i.e., from standing, lowering your arm from an overhead position back to your waist) |

| Eversion | The lateral rolling of your feet (i.e., towards their outside edges) |

| Inversion | The medial rolling of your feet (i.e., towards their inside edges) |

| Extension | The opening or straightening of a joint (i.e., straightening your arm at the elbow) |

| Flexion | The bending or closing of a joint (i.e., bending your knee) |

| External Rotation | The turning of a limb away from the center line of the body (i.e., from standing, rotating your leg at the hip joint so that your foot turns outwards) |

| Internal Rotation | The turning of a limb towards the center line of the body (i.e., from standing, rotating your leg at the hip joint so that your foot turns inwards) |

| Pronation | The turning of a hand or foot medially, or towards the center line (i.e., turning your hands palm down or putting weight on the inside of your foot) |

| Supination | The turning of a hand or foot laterally, or away from your center line (i.e., turning your hands palm down or putting weight on the outside of the foot) |

Why Should You Learn the Planes of Motion?

When you’re designing a workout program for yourself — particularly if your goals include athletic performance, pain reduction, and longevity — it’s beneficial to consider the planes of motion in which your exercises occur, not just about the muscles you’re training.

By now you know that most gym movements — and workout programs — are sagittally dominant (just stroll by the cardio area in any gym and the proof is right there). This isn’t bad — running, stair climbing, squatting, lunging, and cycling are all great exercises.

But such sagittal movements don’t fully stimulate your stabilizing muscles, particularly in your lower body. Over time this can lead to injury. So you’ll likely extend your healthspan in the fitness trenches by including some frontal and transverse plane movements in every workout as well.

Workout programs on BODi are all designed to move you through the three planes of motion while emphasizing compound (multi-joint) exercises, helping you feel fit and strong in everyday life.

A Caveat to the Planes of Motion

The planes-of-motion model isn’t exact; no human movement occurs exclusively in a single plane of motion, and you could probably quibble with the categorization of nearly any movement.

An overhand-grip pull-up, for instance, could be described as a sagittal move because the elbows travel forward relative to the trunk. But if your elbows tend to travel outwards instead of forward, that makes it more of a frontal-plane move.

Our bodies aren’t made up of right angles, straight lines, or hard edges. Every time you take a step forward or back — a sagittally-dominant movement — the joints of your knees, ankles, and hips also move subtly in the frontal and transverse planes to absorb forces traveling up through your skeleton. Every movement you perform occurs on all three planes.

The answer to this quandary? Don’t worry about it. Planes of motion are approximate.

The post Move Smarter by Learning the 3 Planes of Motion appeared first on BODi.

0 Comments