If you want to build stronger legs, don’t overlook the importance of learning a little bit about your leg muscle anatomy.

No, you don’t need a degree in biology to build a great physique. But a basic understanding of the muscles in your legs can help you understand which exercises will be most effective — and which are an injury waiting to happen or a flat-out waste of time.

At the very least, you’ll understand exactly what an instructor means when they say, “Feel this in your quads.”

Ready for a guided tour of your the upper and lower leg muscle anatomy? Read on.

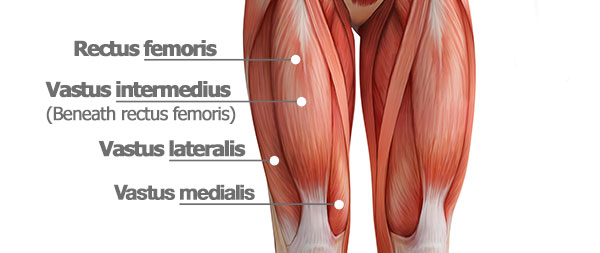

Quadriceps

The quad muscles— which form the meaty mass on the front of your thighs — are among your strongest muscle groups, and play a critical role in athletic activities.

Together, these muscles straighten your knee, stabilize your knee joint, assist in flexing your hip (drawing your knee towards your chest), and help absorb force when you land after jumping or leaping.

True to their name, the quads consist of four major muscles:

- Rectus femoris. This muscle runs from front of your hip to the quadriceps tendon (the fibrous band above your kneecap), crosses both the hip and the knee joint, and assists in hip flexion.

- Vastus lateralis. This is the largest quadriceps muscle. It lies to the outside of the rectus femoris and runs from the outside of your hip to the top of the outside of your kneecap and the quad tendon.

- Vastus medialis. This teardrop-shaped muscle just above and to the inside of your kneecap, helps stabilize the knee joint during athletic movement. It runs from your inner thigh to the quad tendon.

- Vastus intermedius. Hidden by the other quad muscles, this lies underneath the rectus femoris and runs from the front of the thighbone to the quad tendon.

“People try to isolate the individual quad muscles, but they’re all controlled by the same nerves,” says John Rusin, DPT, a physical therapist and elite fitness coach.

That means they all activate at the same time. Some key exercises for the quads include any movement where your knee extends under resistance — especially all types of squats, lunges, and split squat variations. (Rusin recommends the Bulgarian split squat in particular.)

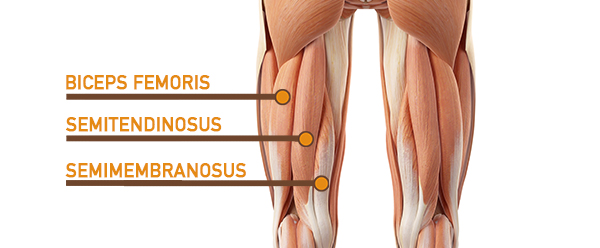

Hamstrings

Located on the back of your thighs, your hamstrings perform the opposite function of the quads, bending your leg at the knee joint and assisting your butt muscles in extending your hip joint, pushing your thigh backward.

Each time you take a step, the hamstrings move from a stretched position to a contracted position. During a hard run, this happens in a split second. If the hamstrings aren’t strong, this fast contraction can lead to injury.

There are three hamstring muscles, all of them originating at the ischial tuberosity (the bones you sit on):

- Biceps femoris. This muscle runs along the outside of the back of your thigh and attaches to the top of the fibula (the smaller of the two bones of your lower leg).

- Semitendinosus. Located just to the inside of the biceps femoris, this muscle attaches to the tibia (the larger lower-leg bone).

- Semimembranosus. This muscle lies to the inside of the semitendinosus and also attaches to the tibia.

“Unlike the quads, the hamstrings are activated by different nerves,” says Rusin. “So it’s possible to emphasize different hamstring muscles by altering your foot positioning.”

A narrower stance on a stiff-leg deadlift, for example, targets the outer hamstrings, whereas a wider stance targets the inner hamstrings and adductors.

Effective hamstring exercises often work the glutes in conjunction with the hamstrings. Some good examples are hip thrusts, hyperextensions, bridges, and deadlifts of all kinds.

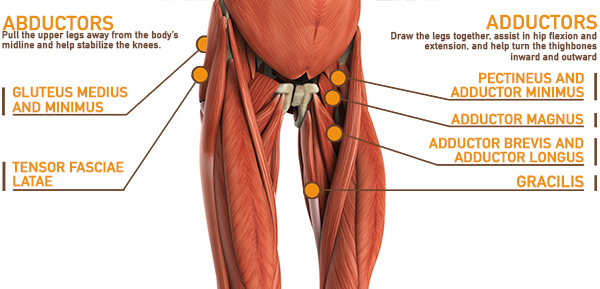

Adductors

When it comes to the upper leg muscle anatomy, adductors often get overlooked, but they’re a stealth power-player. Their function seems simple: Squeeze your knees together and boom, you’re contracting the adductors.

But adductors also contribute to hip flexion and extension — actions mainly performed by the quads and hamstrings — as well as in turning the thighbones inward and outward.

Such versatility makes the adductors crucial in movements like squatting, lunging, running, jumping, and changing direction.

The sail-shaped adductors originate on the underside of the pelvis, and then attach to a line running along your inner thigh.

- Pectineus. The uppermost — and shortest — of the adductors, this attaches high on your inner thigh, near the hip joint.

- Adductor minimus. This muscle is just below the pectineus.

- Adductor magnus. One of the largest muscles in the body, this attaches along the linea aspera, a line running vertically along the inside of your thighbone.

- Adductor brevis and adductor longus. These adductors trace a similar path, reinforcing the action of the broad central portion of the adductor magnus.

- Gracilis. This cord-like muscle runs the length of your inner thigh from your pelvis to the inside of your knee.

The adductors work virtually any time your legs are active, whether for standing, squatting, lunging, and most other leg moves.

You can work them directly with inner-thigh leg raises and Swiss Ball squeezes.

Abductors

The abductor muscles perform the opposite function to the adductors, pulling your upper legs away from your midline.

Abductors are located on the upper portion of the outside of your thighs and hips, anchoring above on the pelvis, and below at various points on your outside thigh.

Like the adductors, the abductors are also responsible for stabilizing your knees during athletic and everyday movement.

When you run, jump, squat, or lunge, for example, your abductors prevent your knees from collapsing inward.

- Tensor fascia latae (TFL). This is the abductor closest to the surface. It runs from the top of your outside hip to the top of your outside thigh, connecting with the IT band, a thick strap of connective tissue running from the outside of your hip to the outside of your knee.

- Gluteus medius and gluteus minimus. Supporting players to the gluteus maximus, these muscles sit above and slightly behind the TFL, and run from the outside of your hip bone to the greater trochanter, the bony protrusion on the outside of your hip.

Any time you push your legs outwards under resistance, you’re working the abductors. Banded walks are perhaps the most direct abductor move, but sumo squats, deadlifts, and ballet plié variations are also effective abductor moves.

But you won’t build much muscle mass in the abductors: “These muscles are paper-thin,” says Rusin. “You’re best off training them as stabilizers in single-leg exercises.”

That means — yes — more lunges, step-ups, split squats, and the like.

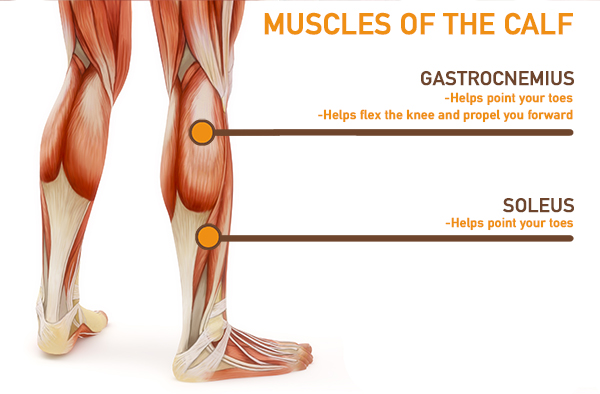

Calf Muscles

As far as the lower leg muscle anatomy goes, the major muscles include two calf muscles and one shin muscle.

They’re responsible, respectively, for extending your foot (pointing your toes) and flexing your foot (pulling your foot towards your shin).

- Gastrocnemius. The larger, two-headed muscle on the back of your lower leg runs from the condyles (bony protrusions) on your thighbone to the Achilles tendon.

- Soleus. Originating below and beneath the gastrocnemius is the soleus muscle, which extends your foot when your knee is bent. Unlike the larger gastrocnemius, however, the soleus does not cross the knee joint.

- Anterior tibialis. This muscle — found on the front and to the outside of your shin, running from the top of your tibia (shinbone) to your ankle — flexes your foot or raises the back of your foot upwards.

Any time you take a step — whether you’re sprinting downfield or window shopping — these muscles spring into action. Work them with all varieties of calf raises, but be sure to include some standing calf raises.

“The biggest calf muscle — the gastrocnemius — works hardest when your knees and hips are straight, and you point your foot as much as possible,” Rusin says.

Seated calf raises focus primarily on the soleus.

The post Leg Muscles: Anatomy and Functions appeared first on The Beachbody Blog.

0 Comments